The stereotype of a “ski bum” often evokes images of longhaired, dope smoking miscreants living in vans and doing as little actual work as possible, and those dudes most certainly exist, but the real evaluation of a ski bum is to gauge just how hard they will work to achieve as many days on snow as possible.

For Whistler trailblazer Toshi Hamazaki, the first step was to learn English, in a month.

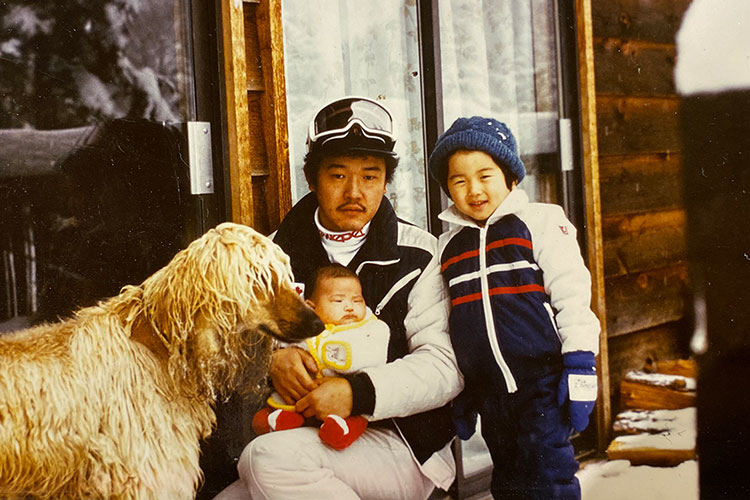

“My dad had been a ski patrol in Japan and a guide in Austria and Norway,” says born-and-raised Whistler skier Yosuke Hamazaki. “In 1970 he answered the call to come to Canada as a ski instructor for this new resort called Whistler. He spoke German, Austrian and Japanese but he couldn’t speak English when he first applied to instruct. He didn’t get the job so he did a month of night school in Vancouver where he lived in the off season and tried again. And he got it.”

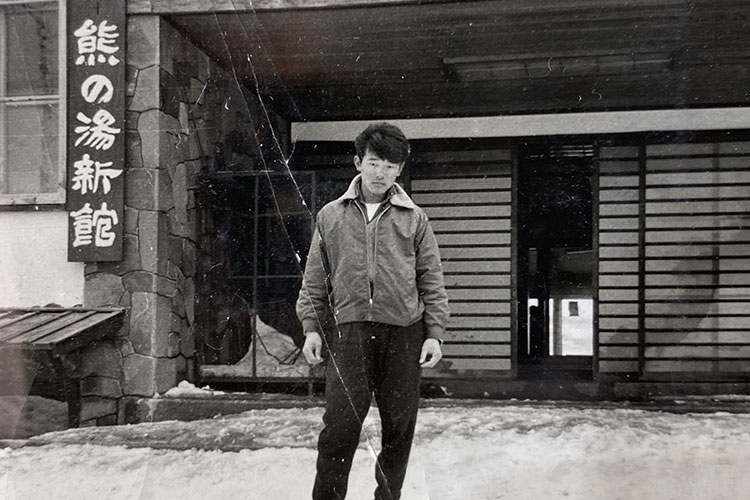

By 1971, Hamazaki had moved to Whistler full time, instructing and helping introduce the resort to Japanese skiers through his connections with television and ski publications back home.

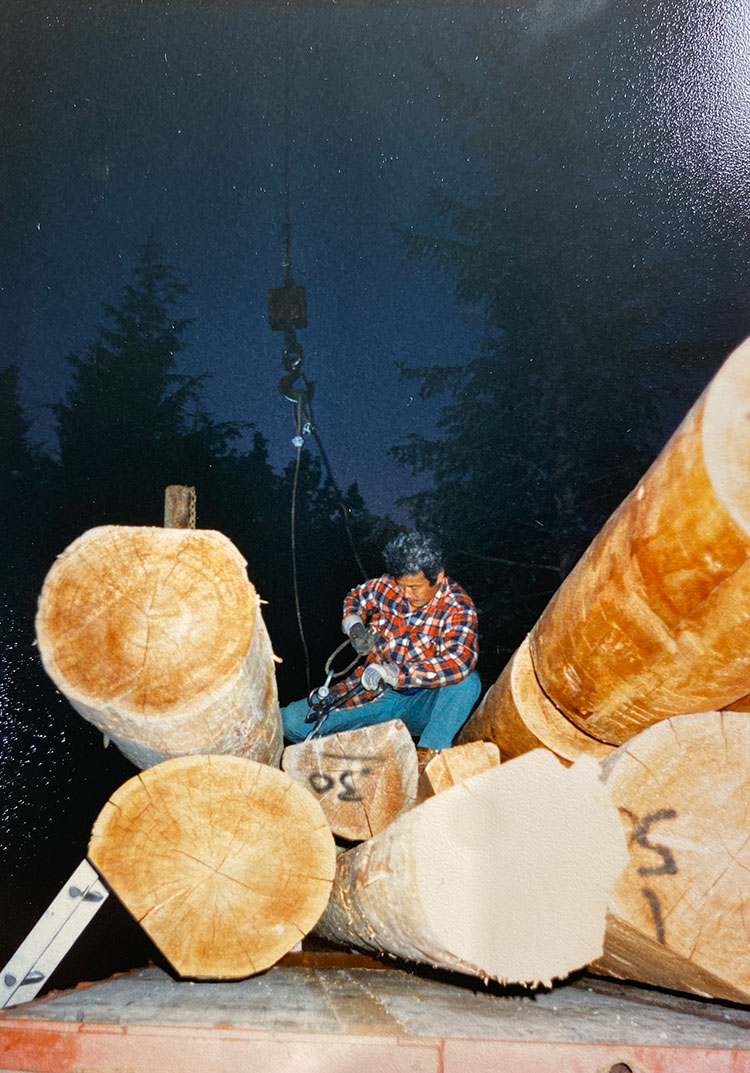

Whistler’s reputation as a ski paradise saw more and more ski bums moving to town and building A-frame cabins and ski shacks. Hamazaki was inspired, so he headed back to Vancouver for another couple of months of night school, for carpentry this time, and returned with enough skill to build his own home in Canada’s hottest ski resort.

Shortly after, he met Setsuko, a young Japanese woman living in Vancouver. She made the move to Whistler and the couple’s first child (Yosuke) was two years old by the time Blackcomb Mountain opened in 1979.

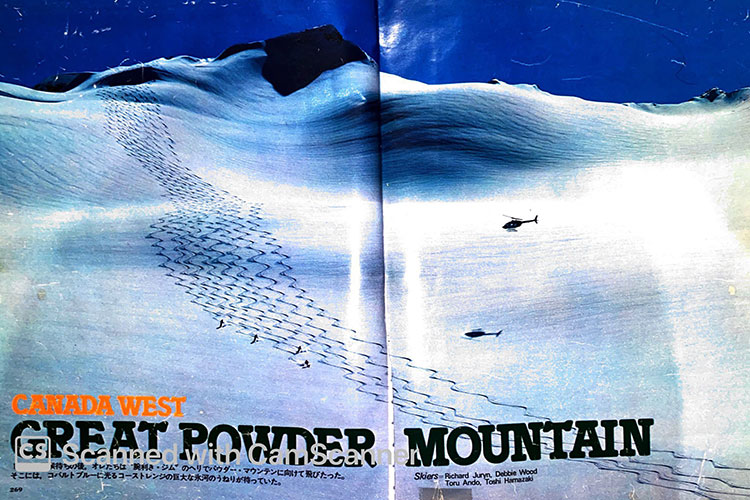

“He was a really adventurous guy,” Yosuke recalls. “Totally fearless and he always wanted to see something new and different. He started a heli-ski company to open up more local terrain and started the first gift shop in Whistler. Some of my earliest memories are my sister and I kind of living in the back of these shops and getting to meet people from all over the world. My dad took everyone in and really wanted people to feel welcome. I remember once the ex-prime minister of Japan came over and my dad picked him up at the airport himself, we drove up with a bunch of secret service guys following us in another car. My dad wanted it to be as authentic as possible.”

Of course, life can sandbag even the best-laid ski bum plans, and young Yosuke found a way to challenge his father early on.

“I didn’t really like skiing at first,” he admits. “But dad was passionate about taking me up. There was a rope tow at Rainbow Mountain, so we spent a lot of time there. Eventually I got up to speed, but it took a lot of patience on his part.”

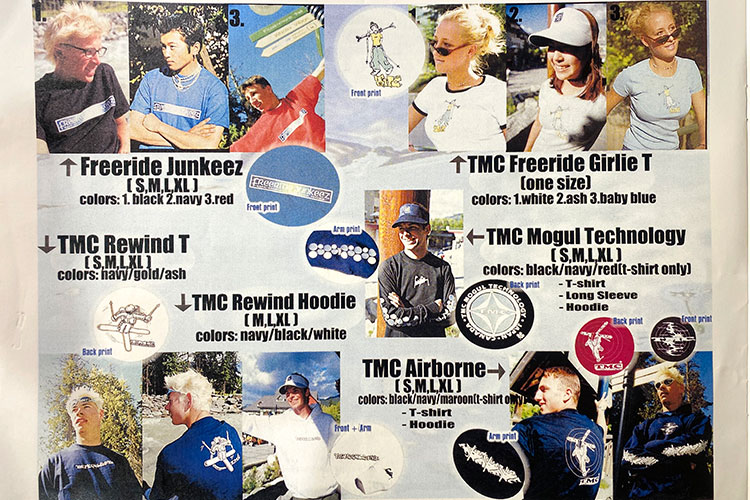

By the time he turned 16, Yosuke was a competitive mogul skier and the roots of the freeskiing revolution were beginning to take shape. Recognizing the spirit of adventure and the progression of a sport he loved, Toshi gave his son some space in the upstairs of the family ski and gift shop (you could get your skis sharpened, buy an authentic Cowichan sweater and some postcards at the same time), and North America’s first freeski store was born.

“It was a kid’s dream,” Yosuke says. “Just what me and my friends thought a cool ski shop would be like, really mogul heavy at first but it was just a bunch of us trying things, designing shirts, doing crazy stuff and going with the flow, just building it ourselves. My dad let me make my mistakes and his message was to always put one hundred percent of yourself into everything you do, because if you do your best it makes you better whether you succeed or fail. He used to always say, ‘Believe in the path you choose with your heart.’”

Toshi Hamazaki passed away in 2015 but his message, spirit and family is still going strong in Whistler today. Yosuke’s shop, TMC Freeriderz, continues to stoke the fires of local and visiting freeskiers (and also sells the best toques in town) and that sense of adventure and community inclusiveness he helped build is as valuable as ever.

“My sister and I, we were very lucky to grow up here,” Yosuke says. “Whistler kids are always meeting people from all over the world and the minute you get here it means you’ve escaped the norm and created an adventure for yourself. I think that is what my dad loved the most. He used to say, ‘if you want to be just like everyone else that is all you will ever be. But if you try harder, open up more, adventure deeper, there is always another place you can get to.’”

And if that isn’t the perfect ski bum philosophy, it’s sure not far off #WhistlerNice.

Toshi’s family and friends compiled the video below after he passed in 2015. Some great glimpses into vintage Whistler and one of the pioneers who helped it grow.

Toshi Hamazaki – A Whistler Mountain Life…RIP 1941-2015 from Yoski ham on Vimeo.