This third installment, Snowboarding Legends are Born and Snowboarding Booms, is part of an ongoing series digging into Whistler’s past. Get up to date with Part 1: The Beginning, Part 2: Dual Mountain and Part 4: Fun and Games.

1987- The New Style

Like many mountain towns, Whistler’s history is chock full of wild characters, forgotten legends and stories that sound almost too incredible to be true. But one thing is certain, everything, all of it, was amplified with the arrival of snowboarding in the late 1980s.

While it seems hard to imagine now, snowboarders were banned from most ski hills in the 1980s. Blackcomb Mountain, the industry’s newest heavy hitter, was the first major resort in British Columbia to recognize the potential of an entire new segment of the population looking to buy lift tickets. They welcomed the single-plankers with open arms for their 1987-88 winter season. As young snowboarders began flocking to ride the best terrain in the country, Whistler began to evolve.

“If you were good and you lived in anywhere in Canada you ended up in Whistler,” says legendary snowboard photographer Dano Pendygrasse in First To Go Up, a short documentary about Whistler’s early snowboard history. “If you wanted to make it as a snowboarder, you ended up in Whistler.”

And so a new tribe began to form in town, with roots in skateboard, surf and punk culture. Many Whistler locals also took to the new sport (because really, there is no better tool for riding the deep Coast Mountain powder than a snowboard) and soon even old-school Whistler Mountain, who continued to ban snowboarders until the 1990 season, had to admit the sport was here to stay.

And we should all be thankful that it did. Snowboarding saved skiing (fat skis are mini snowboards right), it doubled the number of people buying lift tickets, and perhaps most importantly, it brought an influx of women into a town that previously suffered from an incredibly lopsided gender ratio (the term “sausage party” is an apt description). Certainly, there were some tense moments that kind of resembled miniature turf wars outside a classic all-night Creekside convenience store called Food Plus, but in the end everyone realized we are all here for the same reasons, to get outside and have fun with people who also enjoy fun. And the mountains are always truly in charge. By the turn of the millennium, Whistler skiers and snowboarders were riding together in harmony (literally, dropping lines into Harmony Bowl… but we’re getting ahead of ourselves.)

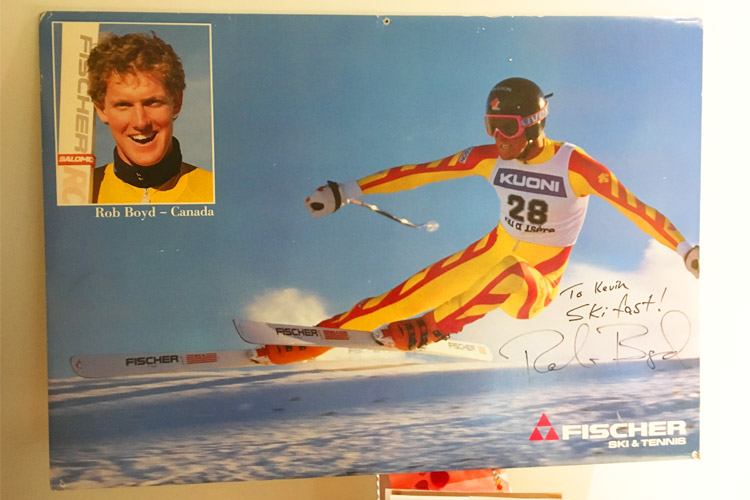

Rob Boyd Wins

Skiing racing was still the coolest game in town in February 1989 when the World Cup Downhill rolled into town for its only Canadian race. And although the Europeans were owning the podium in all events that season, everyone in Whistler knew local racer Rob Boyd was fast, and on home turf.

Boyd, just 23-years old at the time, started his raceday in typical Whistler fashion—he snuck in a nice morning pow line to get the blood pumping. “I looked over at the top of Franz’s Meadow and there was a nice little chute there that hadn’t been skied,” He told the Pique Newsmagazine in a story celebrating the 25th anniversary of the race. “So I skied over to the old Peak Chair, got off midway and traversed along the ridge there, found my line and down through the powder I went, face shots. Then I got back to the top, got ready for my run and did what I did.”

What Rob “did” was win the race, the first Canadian man to ever win a World Cup race on home soil. For Whistler locals and visitors who’d made the drive up to watch, it’s perhaps the most famous 2:10:03 minutes in the history of the town. Followed by the biggest party Whistler had seen to that point and a lifetime of inspiration for young local skiers to ski fast (and take the pow run when you can.)

The 1990s

Alongside the snowboarding boom (which also gave us an incredible skateboard park) and a strong American economy, word began to get out about Whistler’s awesomeness. Whistler Mountain’s Village Gondola focused all the attention on the “new” pedestrian Village while numerous magazine awards, highlights in ski/snowboard videos and the rise of a little sport called freeride mountain biking began to bring adventure seekers to town all year long. Slopeside parking lots transformed into giant hotels (both the Pan Pacific and Westin used to be epic parking lots, $5/day just steps from the lifts.) New chairlifts opened new terrain–Whistler’s Harmony Express started turning in 1995 and Blackcomb had already expanded over to Crystal Chair and the Glacier Express zone. Life in Whistler was good in the 1990s, especially for the epic snow winter of 98-99, which was famously caught on film in local company Treetop Productions’ first film, Clearcut.

Whistler Local Legends: Rabbit

Of all the great characters to grace the Whistler valley over the years, few (if any) are as ubiquitous as John “Rabbit” Hare, who epitomized the ski bum lifestyle.

Born in England in 1932, Rabbit eventually ended up selling suits in Vancouver in his early 20s, a profession that may have contributed to his debonair style and love of dressing up in later years. He arrived in Whistler in the 1970s, fell in love (at the Boot Pub apparently) and started a family. The classic Rabbit story is how he lived with his wife (Rocky) and three kids in a hut at the top of Whistler Mountain, because his job was to get the lifts running each morning. Imagine waking up each morning and skiing to the valley to attend school!

Loved by all and easily recognizable for his wild white hair and beard, Rabbit was almost like a ski bum Santa Claus spreading good will and a solid party vibe throughout our snowglobe community. When he passed away in 2002 a piece of the original Whistler spirit went with him. Thankfully, some wise souls made a commemorative poster with these now-famous words of ski bum advice, attributed to John”Rabbit” Hare: “Leave no turn un-stoned.”

Big snow and new lifts made for success. A booming Village soon meant an expanding Village, the elementary school (named after Whistler pioneer Myrtle Philip) was torn down to accommodate the Marketplace and the Upper Village began pushing north from the Blackcomb base. By the end of the decade, Whistler and Blackcomb had merged into a single corporate entity, Creekside’s legendary après spot Dusty’s was gone (replaced by a bigger, better but still not the same Dusty’s) and Whistler for all intents and purposes, had arrived. By the time Y2K arrived no one really noticed (it was snowing too hard). But then someone started talking about hosting the Winter Olympics…

Stay tuned for the next installment of the People’s History of Whistler, and be sure to stop in to the Whistler Museum and Archives to check out their new photographic exhibition with even more shots from back in the day. If all this talk of skiing and snowboarding has you jazzed be sure to get up here for official mountain opening day. And for all manner of winter vacation planning, local tips and ski packages Whistler.com is the place to go.