This second installment, Ski Bums, Marmots & Dual Mountain, is part of an ongoing series digging into Whistler’s past. Get up to date with Part 1: Beginnings, Part 3: Snowboarding and Part 4: Fun and Games.

Winter Comes to Alta Lake

Already a popular fishing and summer destination, by the early 1960s the community of Alta Lake had begun to attract attention in the winter as well. Inspired by the 1960 Winter Games in Squaw Valley, a group of visionary Vancouver businessmen began toying with the idea of bringing the Winter Olympics to British Columbia. All they needed was a place to host them.

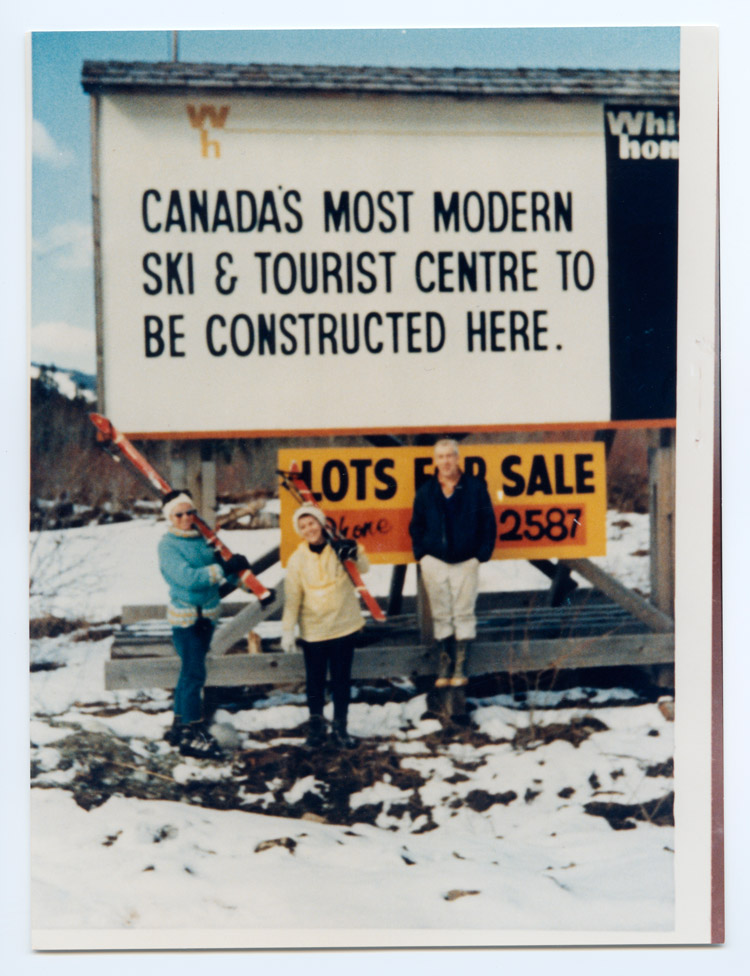

Led by a Norwegian transplant named Franz Whilhelmsen, the Garibaldi Olympic Development Association chose London Mountain on the southeastern shores of Alta Lake as the best potential site. Despite there being no roads, electricity or water and sewer service in the valley Garibaldi Lifts Limited began planning a new ski area with a big future in 1962.

In 1965 London Mountain was renamed Whistler Mountain. Some say it was after the whistling sounds made by hoary marmots that lived on the upper slopes, others claim the name was inspired by the whistling sound created by the wind howling down the mountain’s north-eastern slopes (aka Singing Pass). In any case, a treacherous dirt road went in and construction began in the area near Whistler Creek.

Whistler’s First Gondola and How Creekside Began

“I drove up in a torrential rainstorm in late October 1965,” legendary Whistler local Cliff Jennings said in an interview with Mountain Life magazine. “The road north from Squamish was still under construction and you had to drive across the Daisy Lake Dam. Eventually I came to a big dirt parking lot with foundations going in for the gondola barn. I asked about the boss and someone pointed me to a guy filling sandbags. I was just out of engineering school so I asked if there were any jobs available — he handed me a shovel. Whistler Creek was going wild— just water everywhere–and they had just poured the concrete.”

But the Garibaldi Lift company got the job done and Whistler Mountain officially opened on January 15 1966 with a number of lifts including a 4-person gondola, the original “Red” chairlift, two T-bars and all that incredible coast mountain powder we still enjoy today. As those first gondolas shuttled eager skiers up the mountain, one thing was certain: change was coming to Alta Lake.

The Legend of Seppo

Whistler has always attracted great people but one of the town’s most storied is Seppo Makinen, a Finnish logger who met Franz Whilhelmsen in Vancouver in 1962 and got the job cutting or leading the crew that cut nearly all of the very first ski runs on Whistler Mountain. Seppo’s massive home (conveniently located midway between the ski hills and the Boot Pub) became an impromptu hostel for anyone who arrived in town with a good attitude and little else.

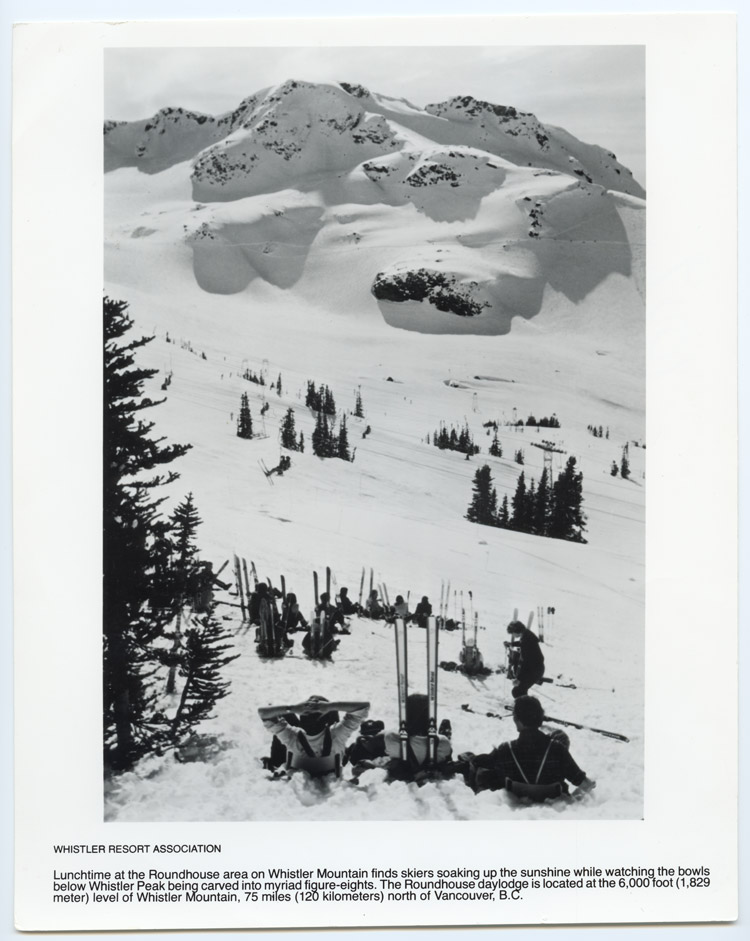

Seppo passed away in 1999 but the last run he ever cut on Whistler Mountain still bears his name and every pow day locals and guests alike get to blast down Seppo’s and get a taste of the freedom and passion for the mountains Makinen embodied so well. Seppo’s in the Roundhouse remains an excellent spot to raise a glass to powder days and remember to thank those early visionaries of the sport.

Ski Bums, Squatters & Toads

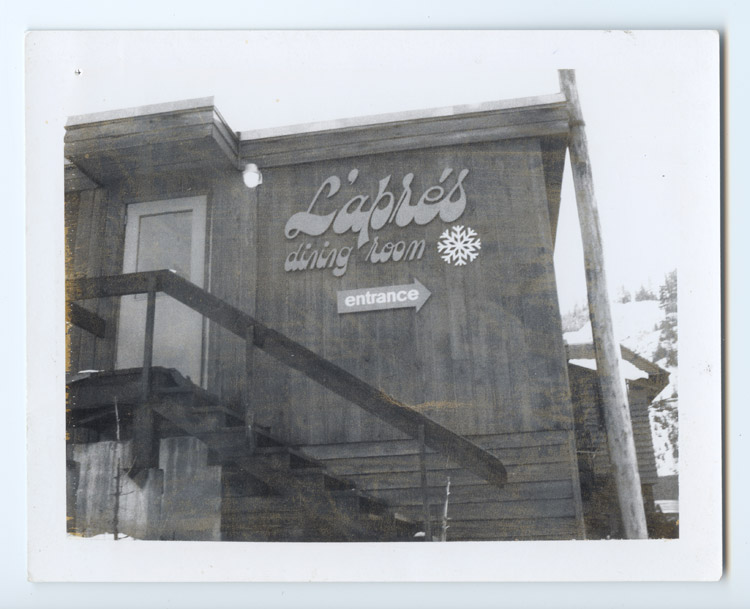

The Garibaldi business crew didn’t get their Olympics (they were Canada’s official bid for the 1976 Winter Games but Montreal won the Summer Games the same year so that squashed that). But as word spread about the new ski hill, deep snow, heli skiing and general freedom of the hills at Alta Lake, the community expanded in every direction. Condos and lodges were thrown up near the lifts in Whistler Creekside and hippies, free spirits and ski bums began squatting on crown land.

The most famous Whistler squat was Toad Hall, a large barn-like compound out at the north end of Green Lake. There was another community of ski junkies putting homes up on the edge of Fitzsimmons Creek in the forest between the local garbage dump and the logging camps on Blackcomb Mountain. It was a time of legendary parties and even more legendary characters and no contemporary Whistler ski cabin is complete without the infamous “Toad Hall” poster, featuring a selection of Whistler’s finest ski bums posing nude in front of their home in the days before it was torn down in the name of progress.

Progress

By 1975 the British Columbia Government had caught wind of Alta Lake’s growing popularity and summer/winter tourism potential and The Resort Municipality of Whistler was created. Cliff Jenning’s daughter Sara was the first baby born in town under the new name (awesomely, Sara still lives here and runs the Whistler Food Bank). Slowly (and relatively peacefully) the squatters and ski bums were either nudged further into the forest or folded into civilized society.

With renewed attention to profitable growth, plans were soon drawn to develop Blackcomb Mountain into a second ski area, with a European-style pedestrian Village built where the bases converged. That the land was currently a garbage dump populated by black bears and squatters scavenging building supplies posed only a temporary problem. The wheels of progress were spinning and the tempo of life in the Whistler Valley jumped up a few notches. There was still no shortage of nudity, however, from the annual May Long weekend wet t-shirt contest at the Christianna Inn on Alta Lake to the nude dock on Lost Lake. The freewheeling lifestyle still thrived.

Where is Dual Mountain?

With a new Village/construction site at her feet, Blackcomb Mountain opened in December of 1980. Residents and visitors (increasingly arriving from around the world) could choose the classic Whistler Mountain runs or the new, more fall-line oriented trails on “The Dark Side”. Or both. Whistler and Blackcomb offered Dual Mountain lift tickets for anyone wanting to partake in both hills in a single day. Of course, sometimes language comprehension is the first thing to relax on a vacation and for years confused guests would stop locals in the new Village asking, “I know Whistler Mountain, and I can see Blackcomb right there, but where is this ‘Dual Mountain’? I’d love to ski that…”

In the early 80s, few skiers realized just how “new” that upcoming era would get. A few years later Whistler was fast becoming North America’s greatest ski resort, and then the snowboarders arrived….

Keep an eye on The Insider for the third and final Peoples’ History of Whistler but if you want to do more personal research, or buy Peter Volger’s Only in Whistler book, head over to the Whistler Museum & Archives and talk to the real experts. (They might also have the NSFW Toad Hall posters for sale.)